Whenever someone asks me if I’m a sworn translator, or I get a request asking if I can do a certified translation, I find myself launching into a long-winded explanation about what this actually means – which is probably a bit alarming for those who were expecting a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

I decided to write a bit more about this, because the idea of sworn translators is a misconception that continues to circulate around the UK. They sound cool, and they definitely sound like a legitimate example of a translator – after all, swearing is as official as you can get!

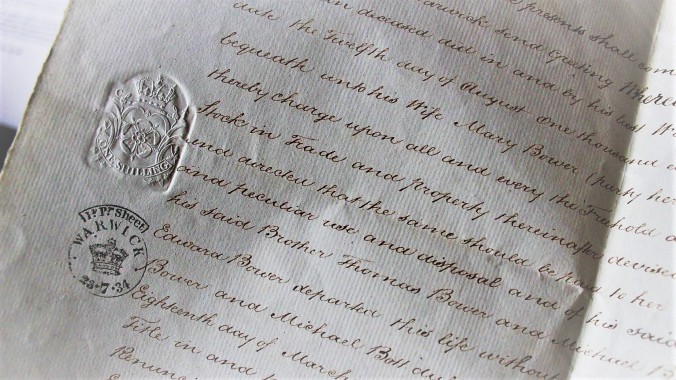

But what often surprises people is that in the UK, there is actually no such thing as a sworn translator, and “certified” can mean different things depending on what the translation will be used for. On the whole, the British translation industry is surprisingly unregulated – anyone can plop their laptop down and start calling themselves a translator. This sounds worrying, but it doesn’t mean that you have to get stung by “unofficial” or poor-quality translations.

It can be hard to find definitive information online, so I have laid out a few points here which I hope will help you work out what is meant by a certified translation, and which type of certification you need (if any). I have also answered a few more FAQs about certified translations here.

So, what’s the deal with certified translations?

The whole idea behind certifying a translation is that the person who translated it is promising that they knew what they were doing, and have translated it correctly.

Because of the unregulated nature of the translation industry in the UK, as well as the fact that different countries have different rules for “official” translations, the requirements for a certified translation vary depending on who needs it.

For example, if you need a document, such as a marriage certificate, to be translated and certified, the UK government says:

If you need to certify a translation of a document that’s not written in English or Welsh, ask the translation company to confirm in writing on the translation:

- that it’s a ‘true and accurate translation of the original document’

- the date of the translation

- the full name and contact details of the translator or a representative of the translation company

This means that the translator provides this declaration with their translation, which holds them accountable to its quality. That’s it. It’s certified.

On the other hand, if you need a translation which is going to be sent overseas for the information of another government, they may request that you get your translation notarised. In this case, the translator’s declaration is sworn in front of a notary public, who adds their own seal. It is important to note that the notary public is not checking the quality of the translation; they are simply confirming the identity of the translator. It’s rare that a translation needs to be checked and notarised by a bilingual lawyer, and finding such a person could be difficult and costly.

Meanwhile, if your document needs to be translated for a British passport application, HM Passport Office gives this advice:

Where a document written in a foreign language is submitted in support of a passport application it should be submitted with an English translation attached. It should be provided by a translator registered with an official organisation such as the Institute of Linguists or the Institute of Translation & Interpreting. A translator who is employed by a recognised Translation company, the latter being a member of the Association of Translation Companies, is also acceptable.

And these institutes are…?

The Chartered Institute of Linguists and the Institute of Translation and Interpreting are both independent, non-governmental organisations, with their own codes of conduct. If they wish to, translators can sit their exam and become a qualified member. In the case of the ITI, this gives them the ability to “certify” your translations with the ITI seal. Here’s the ITI’s line on certified translations:

In the UK, Qualified ITI Members (MITI Translator or FITI Translator) can affix ITI Certification Seals in order to certify a translation. By doing so, this renders the translation ‘official’, in the sense it has been done and/or certified by a Qualified ITI Member.

Generally speaking, translations commissioned by a client are understood to be delivered as ‘official’ in the sense that they have been paid for and are fit for purpose.

So the bottom line is: if it’s good enough for the end user, it’s good enough.

Then why do some translation companies say that they’re certified?

Some agencies claim to be ISO certified, which sounds impressive, but be careful – an agency that is ISO 9001 certified has nothing to do with the quality of the translation services. It applies to quality management system standards, and therefore it’s the company’s processes that are being certified, rather than their products. Since most translators are outsourced rather than being employees of the agency, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the output is of a higher quality.

Meanwhile, ISO 17100:2015 does at least relate to translation services. According to ISO, this certification prescribes that a translator should have “a certificate of competence in translation awarded by an appropriate government body”.

This means that translators do need to prove their credentials (either a university degree, or a qualification from the above institutions) in order to be able to work with these agencies.

However, this still isn’t foolproof – I have often been sent medical and legal documents by ISO 17100-certified agencies that are too far out of my own areas of specialisation. On these occasions I turn the work down, but it’s possible that other translators may decide to have a go at translating it anyway, especially if they’re new or are struggling to find work. This is why it’s sometimes best to approach an individual freelance translator rather than an agency, because at least you’re in direct contact with the person who will be completing your work.

In all, despite this web of rules (or lack thereof), getting a professional translation is often not as over-complicated as it’s made out to be. If you provide your translator with as much information as you can about the purpose of the translation, and they have the appropriate qualifications, it should be money well spent and a straightforward process!

Need more information? I have answered a few more FAQs about certified translations here.

As a member of the Chartered Institute of Linguists, I can help you if you need a certified translation.

Do not hesitate to contact me if you need a document translated and you’re not sure where to turn!

Brilliant. I don’t know how many times I’ve covered this ground, but the urban legend persists. It doesn’t help that my wife is a licensed translator in semisocialist Brazil, where “sworn translator” actually means judicial notice may be taken of the document with licensed translator output. Back when we had Germanic-style hyperinflation, the official fee schedule meant that licensed translators were practically slaves. Inflation was faster than official fee schedule updates.

If I can figure out how, may I reblog your essay?–libertariantranslator

LikeLike

Thanks for reading! Yes, the varying rules do not help matters! And interesting about the fee schedules. I wonder if it’s good, then, that we don’t have sworn translators? After all, someone pointed out to me on twitter that being a sworn translator in Spain, for example, is still no indicator of quality.

Yes, feel free to reblog. I believe the button is under the other like/share buttons under the post. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: 6 ways a translator can help you or your business | Bellingua Translations

Pingback: Certified Translations for UK authorities: Myth-busting FAQs | Bellingua Translations

I believe you need a sworn translator, accredited by the relevant government, to translate documents such as wedding certificate, etc., from English into the language of a country that uses civil law.

In Europe, these include Germany. France, Poland, and the Benelux countries for example.

LikeLike

Yes, many countries do have sworn translators, which is probably what leads to this confusion in the first place.

LikeLike

Thanks for clearing that up, Natalie. I’ve been a self-employed translator for nearly 40 years and (sadly, perhaps) always wondered!

LikeLike

No problem! It is surprisingly hard to find concrete information!

LikeLike

I think we do need this in UK all the same. There seems to be a demand for “sworn” translations into English, which is consequently taken on by non-English translators, “sworn” through their own countries. Due to this demand, agencies often ignore the fact that these “sworn” translators are non-native English, and disregard the fact that UK does not accredit translators..

LikeLike

You may be right…if a client asks for a “sworn” translation for a UK body, are the agencies explaining all this to them, or just giving out the job to people who say they can provide that? And if they are carried out by non-native speakers, are these translations still accepted by the end organisation?

LikeLike

Great post thaankyou

LikeLike